Get clobbered hard enough and you tend to remember it. Just talk to a dozen or so NFL players about last season or, better yet, check with Saddam Hussein. Right after Desert Storm, Saddam was asked if he would accept defeat graciously. He replied, "What's wrong with my feet? You know, I can't hear a goddamn thing."

Our ears were ringing, too, after a similarly humiliating defeat in 1988, when we agreed to a race with our sister magazine Flying. We had long promoted the notion that cars are quicker than airplanes from point A to point B, assuming aforesaid points span about a 250-mile continuum.

So we set out to prove it. Flying obtained a Porsche-powered single-engine Mooney PFM. And we obtained a single-engine Porsche-powered Porsche. Then we raced from Reno to San Francisco. The margin of our agony of defeat added up to 50 humiliating minutes. Ears boxed and ringing Saddam-like, we went home to mull over our thesis. For seven years.

But now, rearmed with staffers whose criminal records stretch fewer than six pages, the time seemed right to challenge Flying to a rematch. Editor-in-Chief J. Mac McClellan and Senior Editor Nigel Moll said this was fine with them, as long as it involved no heavy lifting.

"Your weapon of choice, sir?" asked Nigel, a stately and historic-minded Brit who gave up Bass Ale in America partly because he cannot find any served at body temperature.

"Major firepower, heavy weaponry this time, I'm afraid, Nige," I explained solemnly. "A Ferrari 456GT. Four-thirty-six horsepower, pal. Slightly more than a Fermi II reactor. It costs $225,000, which is how much we'll let you spend on a plane to race us."

Mac and Nigel conferred. Flying's selection was another Mooney, this one called the MSE, with an as-tested price of $227,689. Close enough. In fact, the similarities between the 456GT and the MSE extend marginally beyond your having to be Rupert Murdoch to own either. The Mooney's engine displaces 5.9 liters to the Ferrari's 5.5. The Mooney's top speed of 193 mph would exceed by only 1 mph what the Ferrari engineers promised of the 456GT, although in this assertion the engineers turned out to be about as prescient as the hearing-challenged Saddam. Also, both the aircraft and the automobile are fitted with four tiny seats, paper-thin aluminum bodywork, a cargo area large enough to swallow part of a year-old poodle, a cigarette lighter, and a blinding strobe-light system.

Actually, our Ferrari was not designed with a strobe-light system. But on the way to the race, within 20 miles of the Arkansas birthplace of our current President, the car's pop-up headlights inexplicably began performing a ceaseless up-and-down Watusi dance at an astounding rate, never mind whether the car was running or not. We yanked a fuse. After this, in addition to having no Ferrari headlights, adjustments and no Ferrari horn. Grasping our predicament, fly-boy McClellan turned generous. "To make things fair," he said, "I promise not to use my airplane's horn."

Agreeing on a race route took all of six minutes. The starting line would be Kerrville, Texas, manufacturing site of the Mooney MSE. Just northwest of San Antonio, Kerrville is home not only to Mooney Aircraft Corporation but also to the Texas Mohair Festival, and it is not far from an ostrich farm near the town of Oatmeal. The village of Welfare is just up the road, too.

By coincidence, C/D, spending 14 hours at a crack in the Ferrari's perfectly shaped front seats, was already on its way to Fort Stockton, Texas, so that we might measure the car's colossal velocity on Firestone's oval there. Well, we thought we needed seven miles of oval, naively believing the Ferrari would attain 192 mph. (It went 175.) So there it was, the race route: Kerrville to Fort Stockton proving grounds, a distance of 263.8 miles by land or 235 miles as the crow flies over this semi-arid, bleak Texas landscape, if a crow were a single-engine Mooney.

We assigned C/D Managing Editor Steve Spence to ride in the Mooney with pilot McClellan. Meanwhile, Flying's Nigel Moll would ride in the Ferrari, photographing C/D Executive Editor John Phillips (me) not only at the wheel but also, Moll hoped, later behind impenetrable prison bars.

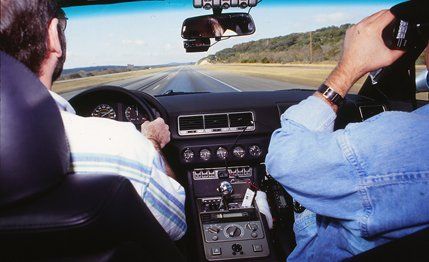

The race began at precisely 10:08 a.m. (don't ask) from the front doors of the Kerrville Holiday Inn. McClellan and Spence had to drive a rental car to Louis Schreiner Field, pull the Mooney out of its hangar, chew a wad of Dramamine, and ensure the MSE's propeller was still partly attached before they could set out. I and the Ferrari, on the other hand, departed at the very moment Moll climbed into the vehicle's back seat and as soon as an anonymous former law-enforcement figure I had secretly hired—we'll call him Smith—climbed into the front passenger seat, where he would work unimagined magic with: (1) a Uniden 520XL Pro CB radio, (2) a Uniden BearTracker 800 BCT7 scanner, and (3) a pair of powerful binoculars with which we could all sate our keen interest in items approaching eastbound in a potentially menacing and constabulary way. Spence's recollection of events appears in italics.

Scene One: The night before, 11 p.m., the hotel bar. McClellan, having sucked the ice clean of any gin residue from martini No. 2, declares he is off to his room to catch the closing act of Monday Night Football.

"Naw, stick around—we're gonna have a tequila chugging contest!" McClellan, who John insists has the determined profile of a pro golfer, does not take the bait, and departs.

Left alone, Smith, Phillips, and I discuss how Mac and his plane, which can go 193 mph without fear of police rebuke and needs to travel 29 fewer miles to the finish line than does the Ferrari, should be properly handicapped in the interests of fair play, a C/D credo.

"Ask the bartender if she's got an ice pick," I suggest. "When he gets to the airport tomorrow—`Oh, shucks, the plane's got a flat tire!' That's reasonable—it happens all the time to cars."

"That would be mean-spirited," Smith observes. This from a Texan, for god's sake.

We have a couple more, then go out to the parking lot to see if the hood of Mac's rental car can somehow be, uh, accessed. Well, lookee here—Mr. Cool has failed to lock up. And look what's in the back seat—a bag just chock-full of his flight charts!

"God wants us to do this," I volunteer.

Meanwhile, the hotel security officer has appeared in the murky darkness. Smith goes over to engage him in a discussion of Saul Bellow's reliance on lyrical metaphor.

Up goes the hood. Oooo, look at all the wires. "Phillips, you worked for Jack Roush—which one goes to the distributor?" I ask.

"Steve," he advises, "cars don't have distributors anymore. But wait a minute, this big thick black one certainly looks critical to its operation." He yanks and yanks, but the Toyota won't give it up. He rips it out.

We depart for bed, convinced tomorrow's race has been evened up a bit.

Scene Two: The driveway entrance of the hotel, shortly before 10 a.m. Somehow, the Toyota is here, packed and ready to go. How can this be? John, who has been out earlier this morning at the Mooney facility helping Nigel take sun-up photographs, palms me a set of keys. "I removed these little guys from the plane's ignition," he giggles. "See if you can give me 30 minutes."

10:08 a.m. Frenzied departure. Mac and I sprint from the lobby. In this footrace, our speeds are nearly equal, although Mac seems to have incurred minor delay by snagging his red cashmere sweater.

I smoke the Ferrari's tires exiting the parking lot but will not so much as chirp them again. Nor will I require, I hope, any of the car's vast 0.90 g of cornering grip. In 10.9 seconds, I pass two cars on the entrance ramp to I-10 and hit 100 mph in third gear, then work my way to sixth. Light traffic, mostly truckers. Unlimited visibility. In the back seat, Moll is affixing a global-positioning navigational system to the Ferrari's quarter window. Then he asks, "Will Texas rangers let me take pictures of you in jail?"

10:08 a.m. Mac and I get in the Toyota, and I muzzle a malicious snort as he inserts the key. This oughta be funny. But the damn thing starts right up! It's seven miles to the Mooney hangar, and the Toyota's engine isn't even missing.

The speed limit is 45. Mac is going 60. "Hey, let's not break the law," I advise. He doesn't slow down.

10:18 a.m. Mac stops at a gate to the Mooney facility. A security guard comes over, has Mac sign in. "Hey," I say, "aren't you gonna ask to see this guy's ID? Maybe he's Hezbollah. A breathalyzer wouldn't be a bad idea, either." No soap.

10:22 a.m. Jacques Esculier, Mooney's young CEO, has walked 50 yards from his office to see us off I ask Mac to make a detailed inspection of the plane and tape-record his monologue, like I have some intention of including it in the story. The plane is pulled out, we shake hands with Jacques, and then Mac discovers that the ignition keys are missing. Oh, no!

Jacques says, "I'll get another set—just take a minute." So much for that. Dangling them aloft, I say, "Gee, look what I found."

10:28 a.m. Mac floods the engine. "Want me to get out and have a look?" I offer. Offer declined. Seconds later, it starts. Cramped inside. A veritable cornucopia of noise, vibration, and harshness. We speak through headsets. "Don't hurt me," I say. (If you ride in one of these seemingly fragile Osterizers, your confidence is increased if the pilot has a nickname like Ironeyes, Smilin' Jack, or Indiana. You don't want to fly with someone named Murray or Lester. Mac will do.)

10:30 a.m. Liftoff comes at 72 mph. We slip through some lacy clouds at 2300 feet and from there conditions are all too perfect: clear and sunny, a wind that hardly registers.

10:35 a.m. My right-seat spotter—dark and brooding—is all eyes, ears, and good advice. A max of 100 mph cresting hills or passing roadside rests, he demands. Then he scrutinizes oncoming traffic: "White Caprice, one mile," he reports, after which, "negative that, just a civilian. But watch this overpass. And don't blow this truck," he warns. I pass at sub-tripledigit velocities, not "blowing" it. Truckers are dangerous. They report four-wheel fast-movers to cops, although the truckers today deem their own 85-mph speeds perfectly safe and abundantly reasonable, despite their nigh-unstoppable tonnage. It is comforting to know that despite its 4200-pound heft, the 456GT's braking nearly equals a Porsche 911 Turbo's.

10:45 a.m. We work the CB radio for all it's worth. "Hey eastbound, come on," intones my spotter in incomprehensibly moronic trucker drawl. "Y'all clear to the 570 [mile marker]," he says. Then the trucker reports in kind—nothing more ominous than a lone county constable on a service road. "Well, hey, y'know, 'preciate it," our man in black replies. "Y'have you a safe one, driver." The trucker thinks we are a fellow trucker.

10:55 a.m. Radio reception has degraded. Because the Ferrari’s roof is aluminum, the magnetic bases of our CB and scanner antennas had to be taped down. We fear the scanner's antenna may have toppled. "Silver duct tape is called '100-mph tape,'" Nigel Moll advises. "It doesn't say anything about 160 mph."

11:00 a.m. We're at 6500 feet, on automatic pilot. We've gone 55 miles in half an hour, with fuel economy at about 14 mpg. I notice we're going about 170 mph, and adding alarm to my tone, I shout, "Hey, slow this thing down!" Mac smiles. And pushes it up to 190 mph.

11:08 a.m. Using his GPS, Nigel calls out our ground speed, our distance from Kerrville, and our distance remaining to Fort Stockton. He announces, "In one hour, you've covered 96 miles." I am dispirited, inasmuch as ambitious truckers and a dozen civilians in Suburbans are running a steady 85 mph out here. "We need to become more serious," I announce. I downshift to fifth and toggle the shocks to "Firm."

11:30 a.m. In just an hour, the plane has flown 137 miles. In a straight line. The freeway bearing the Ferrari is out of sight to the north. I am regretting not implementing Plan C., which was to call ahead to the Fort Stockton airport where Mac had reserved a rental car and inform them that it wouldn't be needed until, oh, six o'clock or so. I could set in motion Plan D, the sudden frenzied breathing and feigned heart-attack ploy, but this guy would not set down. One of his instruments calculates we have just 34 minutes to touchdown.

11:38 a.m. With perhaps a 100-mph closing speed, I overtake a Chevrolet Cavalier that is wandering. I reach to activate the Ferrari's headlights. Then, just in time, I remember that the lights are possessed by Satan and, once activated, will perform a maniacal cyclic ritual of randomly blinding innocent civilians.

11:45 a.m. The sun's warmth is raising tar in I-10's right lane. At about 120 mph, the Ferrari glides and wallows in it, evoking from Nigel Moll the same noise dairy cows make when they are alarmed. I am working in the 100-to-150-mph range. The Ferrari feels perfectly designed for this, Maranello's version of a BMW 850CSi except 7.7 seconds faster to 150 mph.

11:50 a.m. Hey, this guy is taking this way too seriously! He drops down to 4500 feet, where there's more air (long explanation, aeronautics and all that), but it's all bumpy, somewhat violent air. It avails the plane of another 20 mph. I warn, "I'm gonna be sick! On your lap, maybe!" Cap'n Mac just smiles. Steely eyes, RAF moustache, seen the Dawn Patrol 37 times. We're going 184 mph into a headwind of 10. I'm hoping John has heeded my strongly voiced coaching strategy: "Look, Chico, just go 160 the whole way—whattayou care if you go to jail, at least you'll be out of the office for a month!"

11:59 a.m. Interstate 10 stretches out flat and serene as God's own trailer park, almost to the horizon. No vehicles westbound, fore or aft. Hammer down. The Ferrari's speedometer indicates 160 mph. I think I hear antennas tinkling on the roof.

12:02 p.m.The planet's least-used airport appears below. Not a plane anywhere, just a spotless strip of asphalt in the Texas bramble. Mac can't raise anyone in the alleged tower. “Maybe they’ll answer if we go to El Paso," I venture. He puts it down at 12:04.30. He's gone 235 miles in 94 minutes, and it's only cost him 21 gallons of fuel at about two bucks a gallon. An ideal time to recommend a bit of hard-earned unwinding behind the icy rim of a martini or two. Fat chance.

12:08 p.m. "We've driven 201.2 miles in two hours," Nigel announces. "So you're above the 100-mph average, but I think more velocity would be good." Nigel is now evidently into the spirit of the thing, pulling for the wrong team. This, despite the proximity of his boss, who we both hope is still 8000 feet or so above us but not in front of us.

12:10 p.m. Possible trouble. On the CB, a trucker refers to us as "the silver streak," then further identifies us as "some sort of CORE-vitt," which is what all truckers so far think I am driving. "If I had me a cellular," declares the trucker, "I'd call him in. Man, I bet he's doin' 140." Closing supersonically on Fort Stockton, we ignore this threat.

12:12 p.m. Mac now has to travel 13 miles to the finish line from the airport. The tiny terminal is the size of a tract home. Apparently, rental cars are not in big demand here, and ours turns out to be a clapped-out '83 Ford LTD. We climb in and Mac switches on the ignition. What we hear next is not the groan of the starter motor, but the desperate stutter-click of a doomed solenoid. Oh, golly, what a shame. Mac accuses, "Well, you rigged this, too." And jumps out to disappear inside the terminal. A moment later he reappears with the keys to a second car, an equally used-up old Crown Vic. The woman inside has said, "Oh, really? Okay, well try this one." It starts right up. I notice the fuel gauge is on empty. I neglect to mention this.

12:30 p.m. I am thirsty and my palms are sweating. I dump bottled water down my throat and on my hands and wish we had a stewardess.

12:30 p.m. It is silent on the freeway in bright sun. The Crown Vic chugs along. "Do you know where the turnoff is to Fort Stockton?" Mac asks. Gee, I don't. "The woman said there'd be all kinds of signs." Not to worry, Mac. His steely eyes have stumbled on the gas gauge, too. And there isn't a station anywhere on the vast, silent, rattlesnake-infested (I hope) horizon.

Then a huge freeway sign reading "Firestone Road" appears well in front of an exit ramp.

"Think this is it?" Mac asks.

"Naw. Impossible. No way. Wait until you see all kinds of signs."

He turns off. At precisely 12:33.30, he also turns off the car. He's in the visitor's parking lot of the Fort Stockton Firestone proving grounds. It is with a heavy heart I notice the utter absence of a steaming silver Ferrari. When a gauge reads "Empty," is it asking too much for it to actually be empty?

12:35 a.m. Liquid under the dashboard is leaking prodigiously on my left foot. Then, in a blink, we pass Fort Stockton airport on the right, and all three of us strain to see if Mac's Mooney is parked on the desert floor. I can't tell. What I can tell, however, is that my sock is soggy.

Maybe Mac went crazy and performed barrel rolls until Spence threw up, forcing an emergency cockpit hose-down at a distant airport.

12:42 p.m. With the Ferrari's tail hung out, we tear into Firestone's lot in a spray of gravel. To our astonishment and dismay, McClellan and Spence have arrived. They are basking in the sun next to a ratty-looking Crown Vic.

"We've been here only nine minutes," Spence gushes. "I can't believe it." "Better than last time," says Moll, who has now decided that boosting his own magazine's victory is a career-enhancing strategy. He also celebrates that the automotive half of the race was so drama-free and that no photographers are in prison. "Let's make the Ferrari's lights go up and down," he suggests. I ask if, in his spare time, he assembles bombs in his attic.

Our silver 456GT—the quietest, bestriding, most user-friendly Ferrari ever built—has lost the race by exactly 540 seconds. It averaged, for 2 hours, 34 minutes, and 20 seconds, a speed of just under 103 mph. In return for this grand performance, the 456GT gulped 25 gallons of fuel, four more than the Mooney required.

"We must have passed 150 cars and maybe 75 trucks," says Nigel Moll. "And we only annoyed or surprised that lone trucker."

From this, I feel it is possible to conclude one of two things. Either it remains perfectly safe (as long as you are paying attention) to average 100 mph on open stretches of America's interstates, a discovery that will surprise no one except Jerry Brown. Or it suggests we should have more comprehensively dismantled Mac's rental car at the Holiday Inn.

Still, we lost the race. Narrowly. My ears are still ringing.

6:30 p.m. On our airborne return, darkness in this tiny aircraft suggests to me a certain vulnerability, like a paper plane loose on the wind. Mac is no longer racing and has lightened up. Way up. As in, "Hey, you wanna fly this thing?" Not tonight, thanks. He heads downward toward a landing, and I'm wondering just where, since no runway is included in the view—just some rooftops and a Burger King and a dirt road and the dark. We're not much above the treeline when he asks, in his best happy-go-lucky Smilin' Jack voice:

"Hey, can you see a windsock anywhere down there? Geez, I know it's down there somewhere."