If patience were a cashier’s check instead of a virtue, it’d be worth more than a quarter-billion dollars. Conceivably, that’s how much Chevrolet Volt and Nissan Leaf owners, who snapped up more than 50,000 of these plug-in electric vehicles from 2011 through 2012, could have saved had they waited until now.

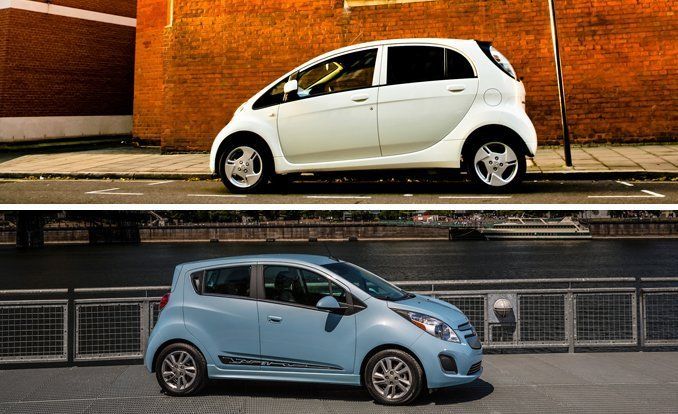

Still, even with $7500 federal tax credits and $8.5 billion in automaker loans being handed out like cotton candy, no one could have predicted the plug-in segment to collapse on itself. In January, when Nissan cut the Leaf’s base price by $6400, that’s exactly what happened. By May, Honda cut its lease-only Fit EV from $389 per month to $259 and dropped the down payment. In June, General Motors undercut Nissan by another $2155 with the 2014 Spark EV and slapped $4000 rebates on 2013 Volts. In July, Ford slashed the price of the Focus electric by $4000, and with continued factory rebates, the 2014 model now costs nearly $15,000 less than it did in 2012. Then, August: Chevrolet chopped $5000 off the Volt’s $39,995 sticker, Smart reduced the lease to $139 per month on its Fortwo Electric Drive, and Toyota offered zero-percent financing on its RAV4 EV. Today, five electric cars cost less than $30,000 before any federal or state tax breaks—and we likely haven’t seen rock bottom yet.

Under ordinary conditions, this shouldn’t have happened. Automakers want to boost average transaction prices, not cut them into pieces like consumer electronics. And even though no one except Fiat CEO Sergio Marchionne has come out and said it, the industry is losing serious money on EVs. The 500E, for example, costs Fiat $10,000 more to build than its $32,500 base price. GM is reportedly losing more than $40,000 on each Volt, and even worse, factory incentives on new plug-ins are even more ludicrous than markdowns on full-size pickups. According to Autodata, GM spent an average of $9504 in incentives for every Volt sold in the first seven months of 2013. In that same time, Mitsubishi quadrupled incentives on its i-MiEV to $9693; Toyota tripled them on the Prius plug-in to $1325. Not even Tesla has made money from building its slick Model S. Price wars are never painless, but in this case, no one’s coming out a winner.

The Land of Milk and Money

Why the self-mutilation? Federal corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) mandates for automakers to reach a 54.5-mpg fleet average by 2025 aren’t really to blame. Due to outdated EPA fuel-economy calculations and exemptions for larger trucks, automakers only have to achieve a combined 36 mpg on actual window stickers under CAFE. Gas prices aren’t a great explanation, either, as they’re way down from record highs in 2008 and show no immediate sign of reaching European levels.

It’s California.

The state’s Zero-Emission Vehicle standard dates back to 1990. It’s part of a complex anti-smog code that requires automakers to sell cleaner vehicles under a cap-and-trade system. But by 2025, the California Air Resources Board wants automakers to allocate 15 percent of their California sales to plug-in hybrid, electric, and fuel-cell vehicles.

“What we’re trying to do is what’s actually achievable and realistic,” says John Swanton, an air-pollution specialist at the state agency. “The market’s going to be as diverse [in 2025] as it is now. We feel those standards are modest enough to let the manufacturer do that.”

That new regulation would also apply to vehicle sales across most of the 10 other states adopting the same California code. Currently, the standard lets automakers bank credits for building zero-emission vehicles and enables them to sell excess credits to other automakers. (Tesla raked in $67.9 million from these trades in the first quarter, a controversial factor in the company’s profitability—it didn’t make a direct profit from its vehicle sales.) In 2015, automakers will have to earn ZEV credits that are equivalent to three percent of their California sales, as opposed to 0.79 percent through 2014. Further down the road, fewer low-emission gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles will count toward those ZEV credits, which means there won’t be enough credits for automakers to trade without building more zero-emission models. With 90 Scion iQ EVs operating in California fleets and 1100 Fit EVs planned to be made available for lease over the next two years, Toyota and Honda will have to build a lot more than their current output.

“Our board looked at what is the reason, what’s going to bring up the economies of scale, to get this going?” Swanton says. “It wasn’t California going, ‘Hey, EVs would be a great idea, we just dreamed it up.’”

Cheaper by the Plug-In

The outlook isn’t so ambitious. Plug-in vehicles account for merely half a percent of all U.S. car sales, and even President Obama no longer proclaims we’ll have one million on the road by 2015. Worldwide, EVs will make up 0.2 percent of all light-duty vehicle production by year’s end, according to forecasts by WardsAuto and AutomotiveCompass. By 2019, it’ll be 0.4 percent, or about four million vehicles.

But even as sales slowly rise, deep discounts and tax credits—not to mention the surge of new technology improvements and significant battery-capacity loss over several years—mean big depreciation. According to the National Automobile Dealers Association, plug-in vehicles depreciated by 31.5 percent in 2012, or more than double the rate of similar gas-electric hybrids and regular cars. By 2014, NADA said this rate could decrease to 27.4 percent, with more-expensive plug-in models likely to be worth less than a gasoline-powered car.

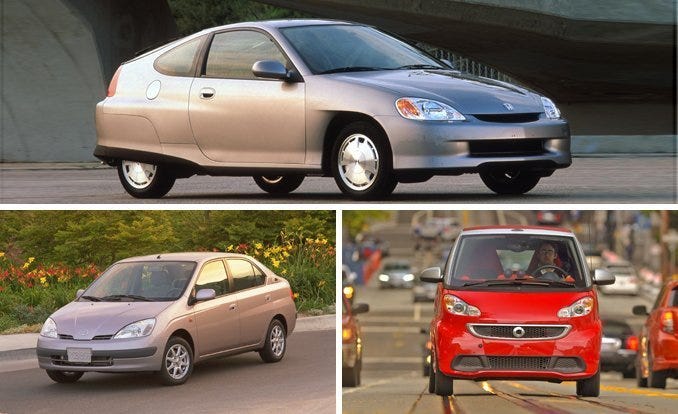

“We expect the rate of depreciation to stay very high, but it will start to slow over the next couple of years,” says Laurence Dixon, the group’s senior automotive analyst. NADA said plug-in vehicles could mirror the similar depreciation rates of the first Prius and Insight hybrids, which saw resale values climb after the first five model years.

This year’s sudden price cuts, along with generous state incentives, have created a price “floor” that essentially wrecks the vehicle’s residual value almost immediately, Dixon says.

“Am I upset? A bit, but extremely happy with my Volt nonetheless,” says Thomas Ta of Dallas, who purchased a new Volt in July. “I am annoyed that GM offered an extra $1000 customer incentive one-and-a-half weeks after I purchased.”

Like the next iPhone or Corvette Stingray, sometimes you can’t wait to have the first one. But if we wanted to own a plug-in hybrid, we’d kill those desires for instant gratification, scour used-car listings in a year or two, and put the savings back in the bank.

Clifford Atiyeh is a reporter and photographer for Car and Driver, specializing in business, government, and litigation news. He is president of the New England Motor Press Association and committed to saving both manuals and old Volvos.