Mr. C.N. Hughes

Chief Engineer, Camaro

Chevrolet Motor Division

30003 Van Dyke Avenue

Warren, Michigan

Mr. James H. Kennedy

Manager, Mustang Development

Ford Motor Company

21500 Oakwood Avenue

Dearborn, Michigan

Gentlemen:

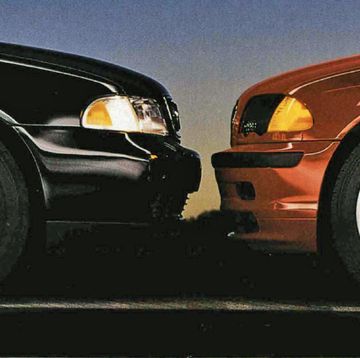

It has come to our attention that American auto manufacturers are now engaged in what is commonly known as a performance war. We have watched with profound interest as one and then the other of you have escalated the battle. Today, both the Camaro and the Mustang have enough power under their hoods to light a small city. The burning question is: Which car is better?

We'd love to provide the answer to that question to millions of car enthusiasts. We hereby invite you to build the fastest possible version of your sporty car for a bumper-to-bumper comparison test. Leave out the air conditioning, power ashtrays, and any other ballast that makes no functional contribution to acceleration, cornering, or braking. Of course, you should build in the best available powertrain and suspension. (We want cars within normal specifications, not factory racers.) Please make the contenders available for our evaluation in Southern California, where we'll run them through a careful technical inspection, followed by our standard battery of performance tests. In addition, we'll hot-lap Willow Springs International Raceway as part of this evaluation. Be forewarned: if either car seems to be fishy, we may be forced to use exhaust-emissions testing as a check for legality. When the results are in and the dust has settled, the victor will be crowned.

So start those assembly lines rolling! And may the best all-American GT take home all our marbles!

Sincerely,

The Editors of Car and Driver

______________________________________________

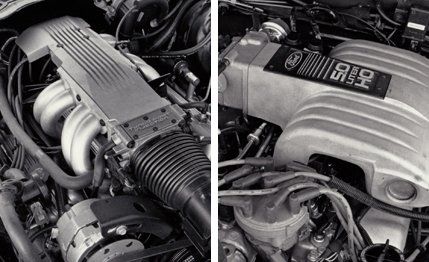

Submitted for your approval are two of the fastest RSVPs ever delivered to our doorstep. From Dearborn came a blood-red Mustang LX two-door sedan (the two-door body is 58 pounds lighter than the three-door hatchback), equipped with the top-of-the-line fuel-injected, 200-hp, 4.9-liter V-8, a five-speed gearbox, and all of the Mustang GT's handling hardware. An AM/FM-stereo/cassette unit and a rear defogger were its only other options.

The Chevrolet contingent anted up their new Corvette-powered missile, the 5.7-liter IROC-Z. This car was scheduled for mid-1986 production for the express purpose of wresting the pony-car acceleration crown away from the Mustang V-8.

In its IROC application, the ram-tuned, fuel-injected Corvette powerplant is rated at 220 hp (10 hp was lost to the Camaro's more restrictive exhaust system). It is backed up by a four-speed automatic transmission, because a manual gearbox hefty enough to handle the engine's torque won't fit. Nor is air conditioning an option in this model. (This keeps the 5.7-liter IROC in the desired EPA weight class.) Because of the complexities of certifying this engine-and-car combination, only 1000 big-engined Camaros were scheduled for 1986 production. Going to so much trouble for so few cars indicates just how badly Chevrolet wants revenge.

The Camaro was almost as light on options as the Mustang, but it did not lack for attention to detail. Our test car's metallic-red paint sparkled with a world-class polish job, and its throbbing exhaust suggested that its engine had been handpicked for battle. All was ready.

The Route

We descended upon LAX to find California cleansed by coastal rains and basking in perfect weather. Our two rorty V-8s and the Golden State's curlicue roads lured us into a Kodachrome morning. Keeping an eye peeled for any Beverly Hills cops, Eddie or not, we rumbled north on U.S. 101 and into 600 miles of point, squeeze, and squirt. The IROC-Z and the Mustang LX found their way onto California 150, through the mountain switchbacks, past Lake Casitas to Ojai. Alas, our best-laid plans to dig deeper into the mountains on California 33 fell through with a landslide, so we settled for a pleasant outdoor lunch at the Nugget in Summerland, near Santa Barbara.

Resorting to plan B, we thundered up San Marcos Pass on Route 154, rattled down Stage Coach Road, and soared again to rejoin our original route. Our heavy metal ironed the sunset's wrinkles into darkness on a snip of California 1, sweeping past Vandenberg Air Force Base to an overnight stop in San Luis Obispo.

Setting off across the next morning's shadows, the Mustang and the Camaro caromed through the rhythmic folds of California 229 and out into great furls of green hills. In 1955, at a quiet crossroads near Cholame, the actor James Dean died when his Porsche augered into a car that crossed its path (C/D, October 1985). We paused to pay homage where Dean suffered his fateful splat, then hammered back to 101 and whirled inland on fabulous, remote California 58. At McKittrick, the town's only gas station was closed, so we refueled ourselves instead, finding a bar with good greasy burgers. Two guys in the next booth looked like roughnecks from the nearby oil fields, but the topic of their conversation was WordStar word processing!

We finally found gas on the pug-ugly, oil-rigged road to Maricopa. Tanks topped, we boomed up the Grapevine Grade on Interstate 5, then east, bedding down at Rosamond, beside Edwards Air Force Base. Here, the right stuff would be sorted in performance tests on and off the Willow Springs road course.

The Test Track

Sometimes one can easily predict the relative performance of two cars by examining their vital statistics. For Example, the Camaro's sleeker bodywork and higher power output strongly suggest that it will outrun the Mustang on the top end; and so it did in our tests, by a 10-mph margin over the Mustang's 132-mph maximum. However, in acceleration, cornering, and braking, the Mustang's lighter weight appears to be a tremendous advantage, partially offsetting the Camaro's edge in both traction and power. In the end, the only way to find the better performer is to set aside the bench racing and conduct careful, head-to-head testing.

In our acceleration tests, the critical difference between the two cars was their off-the-line traction. The IROC-Z puts its energy to the ground with just the right amount of wheelspin to let the engine quickly reach the meat of its power band. In contrast, breaking the Mustang's tires loose is futile, because its traction just goes up in smoke. Slipping the Ford's clutch produces better results: our best runs clocked the Mustang's zero-to-sixty acceleration at 6.2 seconds, a mere tenth of a second slower than the Camaro. As speed increases, the gap widens slightly because of the Camaro's superior aerodynamics: by the end of the quarter-mile, the Mustang has fallen 0.4 second behind the Camaro's 14.5-second clocking. It should be noted that, in flat-out acceleration, the Camaro's firm-shifting automatic transmission gives up nothing to the Mustang's five-speed manual.

The Mustang and the Camaro were also very close in our cornering tests, though they behave very differently at their respective limits. The Camaro edged out the Mustang on the skidpad, 0.84 to 0.83 g, by virtue of its almost perfectly neutral cornering balance. At its limit, the Camaro has a touch of understeer, which can be smoothly shifted to oversteer by applying a bit more power. In contrast, the Mustang corners with pronounced understeer, and its tail can be kicked out only by applying the full brute force of its engine. Through the slalom cones, however, the stability provided by the Mustang's understeer made up for the Camaro's better balance, and both cars managed the same 60.2-mph speed.

The one test in which we measured a wide difference in performance was braking. The Camaro's superior front-rear balance helped it stop from 70 mph in only 203 feet, 19 feet shorter than the Mustang.

The Racetrack

Performance testing on a race circuit requires a blending process: the test subject's acceleration, braking, and cornering capabilities must be carefully assembled by the driver into a combination that will produce the fastest-possible lap speed. In this process, controllability at the limit is every bit as important as the precise magnitude of that limit.

In fact, it was excellent controllability that gave the IROC-Z its big advantage at Willow Springs. The Z's nearly neutral cornering balance and ability to segue smoothly from understeer to oversteer made driving on the track easy. In long, sweeping corners, it was a cinch to choose a line and set the car's attitude by gently caressing the throttle. Upon exiting the bend, more power, along with a bit of opposite steering lock, kept the Z pointed in the desired direction without breaking traction at the rear wheels.

Driving the Mustang was much harder, because it understeered strongly most of the time. Increasing the power in a turn made its front tires grind even more, though a heavy foot on the throttle would eventually break the rear tires' grip. Keeping the tail from getting too far out of line wasn't difficult, but the necessary corrections—lifting off the throttle and straightening the wheel—took their toll on our lap times. The Mustang's tendency to kick its tail out also made it hard to apply power when exiting a corner: a little too much can lead to a tire-smoking, opposite-lock powerslide.

The Mustang's errant tail hindered it through Willow's esses as well. Once broken loose, it tended to swing like a pendulum from side to side as the driver attempted to follow the winding road course. In contrast, the Camaro could be flicked first one way, then the other, with exactly the amount of tail swing desired.

The Camaro also had a noticeable advantage in braking. Thanks to its superior brake balance, we could wait longer before initiating braking for a turn. The IROC-Z's better cornering balance also made it practical to trail the brakes much deeper into the bends.

Despite the shortcomings of the Mustang, it was anything but a handful on the racetrack. We never spun either car, nor did we ever drop a wheel off the track. The Camaro's superior controllability, however, enabled us to drive it a little closer to its limits every foot of the way around Willow Springs' 2.5-mile length. Over a complete lap, that advantage produced an 88.5-mph average speed, nearly 2 mph faster than the Mustang could manage.

The Bottom Line

This is where we come to a fork in the road. Now that we've gone to the trouble of generating a full set of performance-test results, we must ask you to keep them in their proper perspective. This is not a test of numbers alone. The quickest car through the quarter-mile is not necessarily the winner-in this book.

What matters most, we believe, is how the two cars compare in the wider world of day-to-day driving. Every kind of road that separates point A from point B—city, highway, and tortured two-lane—has been factored into this evaluation. Four flinty-eyed commandos set out on a search-but-don't-destroy mission, then sat down to turn their feelings into numbers for the Editors' Ratings chart at the end of this story. The Overall Rating column will tell you which car is the winner in our eyes, but some of the whys and wherefores need explanation.

During this wheel-to-wheel confrontation, the 5.7-liter IROC-Z accomplished exactly what the Chevy engineers intended: it was quicker than the Mustang. The difference wasn't great, however, and besides, there's a lot more to real-world driving than isolated bursts of speed.

The Camaro is less impressive when the whole picture is taken into account. It took our panel of judges only a few corners to discover the Chevy's Achilles' heel: its seats. By the end of our 600-mile road trip, our logbook bulged with complaints about them. The seats—admittedly base equipment, in keeping with our initial request for the lightest-possible car—lacked any hint of upper-body lateral support. Drive the IROC-Z with enthusiasm on a winding road and you'll expend 80 percent of your effort just holding yourself in place behind the controls. The seats even proved subpar during relaxed highway cruising. There is no excuse for such wimpy seats in a car so aggressive.

It's too bad its seats are so awful, because the Camaro is otherwise at its best on fast, twisty two-lanes. The engine feels powerful enough to uproot redwoods. The grip seems nearly limitless—a good ten percent higher than the Mustang's–even though the test track tells a different story. Some testers complained that when you work the Camaro hard, it notches into corners instead of flowing into them, but the firm chassis calibrations keep the body motions under control. There is no treachery, not even when going nosebleed-fast.

The only drawback to zigging and zagging in the IROC-Z—aside from its lousy seats—is the car's size. On very tight roads the IROC seems a good two feet wider than it really is.

The wide-load feel is nothing compared with the rough edges that turn up during more restrained driving. We see no legitimate reason that the IROC-Z's transmission should bang off part-throttle shifts like a B&M drag-racing unit when you're puttering around town. Nor can we abide a differential that howls like a coyote at 50 mph. At 70 mph, the exhaust system of our test car throbbed so badly, we felt as though we were locked inside a 55-gallon drum that was being banged on with a rubber mallet. We also noted that our Camaro lacked useful interior cubbyholes, that its flow-through ventilation was woeful, and that its body creaked.

The Mustang LX has a different set of strengths and weaknesses. Compared with the stunning IROC-Z, it looks like a bread-box on roller skates. Its dash design is from a distant era as well—and this year's high-tech graph-paper pattern doesn't do much to modernize the layout.

The old girl's big advantage in the sheetmetal department is efficiency. Not only does the Mustang notchback weigh in 300 pounds lighter than the Camaro, it also offers seating for four life-sized adults. (The Camaro's rear seat is best left to your Chihuahua.) Unfortunately, the Mustang's shallow trunk can barely swallow a picnic basket, whereas the Camaro's cargo hold will almost handle a picnic table.

To drive the Mustang is to feel its years melt away. The LX's strong suit in this comparison test was its refinement. Its engine is much quieter than the Camaro's, though every bit as impressive. Its body structure is tight as a drum. Its five-speed works effortlessly, and the ability to control one's own gears was a solid plus on the canyon sections of our trip.

The Mustang's ride is more compliant than the IROC-Z's, and in most cases we liked its softer calibration better. When the road surfaces got bumpy, though, the LX's tail bobbed. Here, the Camaro's tighter wheel control gave it the upper hand.

The Mustang's greatest driving asset is its front seats. You sit up like a citizen in this car. The base LX buckets are nicely contoured and reasonably firm—worlds better than the Camaro's sorry thrones. There's nothing here that Recaro couldn't improve upon, but the LX seats at least take most of the work out of going fast on serpentine stretches.

Speaking of handling brings up more pluses and minuses. Compared with the Camaro, the LX could use a lot more feel in its steering. Still, the Mustang is the easier car to drive smoothly when you're in a hurry–at least up to a point. Way out there in the expert zone, at the fringes of adhesion, a bob of the tail or an inadvertent twitch of your throttle foot can trip the LX up. The IROC-Z, in the same situation, just digs in and keeps going.

The LX's more compact dimensions also make threading the needle on narrow roads a lot less intimidating. On the other hand, the LX's brakes are less than confidence-inspiring–and they got mushier as our test wore on. (We suspect a problem peculiar to our test car.)

Both of these machines, of course, are bags of fun. Both can pin you and your honored passengers to the seatbacks like an amusement-park ride, while embarrassing a host of more expensive exotica–and for that they both earn our admiration.

As for king of this particular hill, though, it's a matter of age over beauty: Ford's continual efforts at year-in, year-out improvement have made an older and in some respects, inferior design perform with more polish than the new iron. Our overall feeling is that the 5.7-liter Camaro is more fun for blowing sludge out of your brain on a deserted two-lane, but the Mustang is the better all-around automobile. IN all but the wildest maneuvers, it's more coordinated, more comfortable, and more poised–in other words, a nicer car to live with. We hereby give the win to the Mustang LX by a fender-length.

And that lead is stretched to several furlongs when you factor in the two cars' sticker prices. The Mustang LX we tested comes in at a mere $9956; this could be a record value in a high-performance automobile. The Camaro lists for $16,338. Dearborn has slain Goliath.

But wait. As it turns out, our judgement is rendered moot by a bizarre turns of events. As we go to press, Chevrolet has wimped out for the 1986 model year and decided not to build 5.7-liter IROC Camaros until enough aluminum cylinder heads are available to keep the gas-guzzler stigma off the car. (The bow-tie boys also confess that the 190-hp, 5.0-liter LS9 engine will not get a five-speed during 1986.) Chevy promises that a 5.7-liter, automatic powertrain will be ready for the start of 1987-model production.

So the Mustang wins on two counts: on its own virtue and by default. And in doing so it sets the stage for a rematch in 1987, when it will be back with styling changes, a new instrument panel, and 230 hp to meet Chevy's best effort. Messrs. Hughes and Kennedy, watch your mailboxes.

Rich Ceppos has evaluated automobiles and automotive technology during a career that has encompassed 10 years at General Motors, two stints at Car and Driver totaling 20 years, and thousands of miles logged in racing cars. He was in music school when he realized what he really wanted to do in life and, somehow, it's worked out. In between his two C/D postings he served as executive editor of Automobile Magazine; was an executive vice president at Campbell Marketing & Communications; worked in GM's product-development area; and became publisher of Autoweek. He has raced continuously since college, held SCCA and IMSA pro racing licenses, and has competed in the 24 Hours of Daytona. He currently ministers to a 1999 Miata, and he appreciates that none of his younger colleagues have yet uttered "Okay, Boomer" when he tells one of his stories about the crazy old days at C/D.

Csaba Csere joined Car and Driver in 1980 and never really left. After serving as Technical Editor and Director, he was Editor-in-Chief from 1993 until his retirement from active duty in 2008. He continues to dabble in automotive journalism and WRL racing, as well as ministering to his 1965 Jaguar E-type, 2017 Porsche 911, 2009 Mercedes SL550, 2013 Porsche Cayenne S, and four motorcycles—when not skiing or hiking near his home in Colorado.