HIV response 'at turning point'

- Published

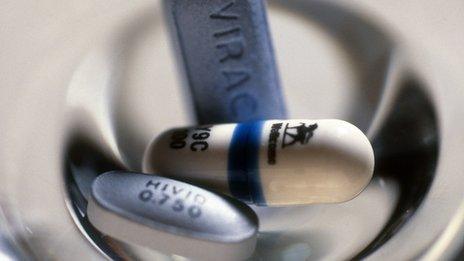

Access to HIV drugs has improved significantly

December 1 is, as it has been every year since 1988, World Aids Day.

Much progress has been made, but in this week's Scrubbing Up, Chris Beyrer, president-elect of the International Aids Society and Michel Kazatchkine, the UN Secretary General´s Special Envoy for HIV/Aids in Eastern Europe and Central Asia warn that we are at a turning point in the fight against the disease.

They are co-chairs of the 'Nobody left Behind campaign', an International Aids Society initiative.

Living in Paris in 1986, Andrée was a drug user with no hope of access to an effective treatment for HIV (since there was none), and no access to harm reduction (since it did not exist).

She had lost her friends and family, she was stigmatised - and she ultimately died a lonely death after a few months in a hospice.

Larissa, from Kaliningrad in Russia started antiretroviral treatment late in her HIV disease, and only because of her privileged contacts, but had no hope of treatment for her hepatitis C.

She had been rejected by friends, neighbours and family. She too was stigmatised - and she had been repeatedly arrested and incarcerated.

But Larissa's story is from 2013, not 1986. While 25 years has passed in the circumstances of these two women, their predicament was depressingly, tragically, the same.

How this can possibly be so, in a period when so much progress has been made?

We seem to have come full circle and now have to face what will certainly be an uncomfortable truth for many of us working in the sector: we have made very little, if any progress, in getting prevention and treatment to those groups of people most vulnerable to HIV/Aids, wherever they are.

These groups people who inject drugs, transgender people and men who have sex with men. They make up the majority of those affected by the epidemic, except in sub-Saharan Africa, where they also make up an increasing share of infections in urban settings.

New obstacles

Against a backdrop of some truly extraordinary responses to the global HIV/AIDS epidemic over the past 30 years, it is both painful but necessary to acknowledge that the response for these groups remains so often a story of indifference and neglect.

Indeed we can compare our failure to adequately address these issues to the situation that prevailed in 2000.

At that time, effective HIV drugs had been available in rich countries for years, but were inaccessible in developing and emerging economies because of cost.

Today, cost is not the primary obstacle: we have drugs and we have proven interventions.

Rather, it is economic, social and political obstacles that prevent them from being made available to those who need them most.

We have plenty to be immensely proud about the global response to HIV/Aids: antiretroviral treatment has been provided to 10m people in developing countries, with notable success in Africa, where 60% of people in urgent need of these medicines now have access to them, something unthinkable just a few years ago.

As a result, at a global level, we are seeing steadily declining rates of new HIV infections: a third fewer in 2013 than in 2011.

Around 1.6 million people died of Aids in 2012, down from 2.3m in 2005.

Of the 25 countries that have achieved a 50% reduction in the rate of new HIV infections in the last 10 years, more than half are in sub-Saharan Africa.

'Turning point'

The successes are due to factors such as some extraordinary advocacy from civil society activists and community mobilisation, courageous and compassionate political leadership and remarkable advances in science and technology which have enabled new drugs and tests to reach parts of the developing world at unprecedented speed and relatively low cost.

This is the Aids response that has generated extraordinary hope: sort of hope we see reflected in recent headlines that predict "the end of Aids", or "a world without HIV", or the possibility of an "Aids-free generation", in our lifetimes.

Sadly, however, this is not the whole story.

One can draw upon an almost infinite supply of statistics that tell the true picture for those most affected by the epidemic: in low- and middle-income countries, men who have sex with men and female sex workers are 19 and 13 times more likely to have HIV, respectively, than the rest of the population.

Men who have sex with men alone account for more than 33% of new infections in China, and projections indicate that this group could make up half or more of all new infections in Asia by 2020.

The fuel for these figures, for the lives being adversely affected, are the recurring themes of stigma and discrimination at the social, cultural and political levels.

Public health access for these groups is being driven underground; there are repressive government drug policies which advocate criminalisation over public health and there is a failure and unwillingness of too many governments to base health policy on the scientific evidence before them.

Growing urbanisation, and the accompanying movement of marginalised groups to cities seeking to explore their sexuality and increased freedom of cultural expression is having an impact.

So too is the transition of many developing countries into middle income status - accompanied by increasing economic and social disparities as well as the sudden ineligibility for crucial Global Fund finance that was previously the backbone of the national HIV/Aids response.

Quite simply we are at a turning point. And if we are honest with ourselves we ought to admit that we are somewhat in disarray.

We don't know quite what it is that we should do.

Here we are, we have all the technology, we have extraordinary scientific progress, and we just cannot translate that into making a difference in these populations.

But it is abundantly clear that there is an urgent need for re-think of how we approach the epidemic.

A failure to do so will mean that there is a serious risk that Aids will become more and more concentrated everywhere.

And that means we will not be able to end Aids.