Before the 2014 Olympics, German automaker BMW reimagined the bobsled, building for Team USA a sleeker, lighter ride. In 2016, it's the Paralympic athletes' turn, as the Bimmer is making them a faster, better wheelchair.

"The idea is the wheelchair disappears and it is just about the athletes," Brad Cracchiola, BMW Designworks project lead, tells Popular Mechanics. "These athletes are truly incredible and work very hard, they just don't have a lot of publicity."

Previous chairs were made of welded aluminum, which doesn't scream high-tech. So ahead of the Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro this summer, the BMW Designworks studio in California set out to upgrade the performance-limiting aluminum racing chair used by Paralympic athletes in nearly every sport, from the 100 meters all the way up to the marathon. BMW had plenty of room to work: Rules require a completely hand-cranked chain (no gears means no mechanical advantage) and mechanically engaged braking (no Bluetooth devices allowed). Otherwise, the chair just has to fit within the lanes.

BMW started the process with a 3D scan of athletes in the current chair and then ran aerodynamic simulations of how the old setup performed. For the new chair, BMW quickly switched to carbon fiber to provide both a greater strength-to-weight ratio than aluminum, and also to open up new shaping possibilities for aerodynamic needs, with the idea to keep the flow of air as smooth as possible and avoid drag-inducing turbulence.

"From a head-on view, we want to keep it all as compact as possible and lined up," Cracchiola says. With the frontal profile minimized and as many components of the chair in line, BMW also created smooth surfaces, akin to the bullet-like shape and smoothness of a shark. "You want the air to hug the surface and move very smoothly."

And it's about more than the chair. Because of the Paralympic style of racing, with the athletes kneeling into the keel and essentially punching the wheel's rims with specialized gloves, BMW also revamped the gloves and now custom 3D-prints them to fit each individual athlete. Because they race this way, the chairs take incredible abuse and also flex during the race. "Anytime the chassis is flexing you are losing energy," Cracchiola says. What's a wheelchair designer to do? "Ideally all of the energy translates to wheel speed and making them faster," he says. "If the chassis is allowing the wheels to snowplow, you are scrubbing your own speed. A stiffer chassis keeps the wheels aligned. It is more about how you use materials. It is about finding the right balance between weight reduction, aerodynamic opportunity, chassis stiffness and durability. You can buy a carbon fiber bike that is extremely light, but one rock kicks the frame and you're done."

From there, designers could move into customizable fit. The old aluminum gave athletes a generic box structure, and they would add foam pads and straps to block themselves in, allowing a lot of room for shifting out of position. BMW took measurements and a custom mold of the legs of each of their four BMW Performance Team athletes to size the chair to fit them using straps and moving parts. "All that is moving is their arms hitting the wheels," Cracchiola says. By making the seat height, knee angle, width and steering device adjustable, BMW can cater to its four athletes and potentially more from Team USA.

We're excited to see these creations roll into Rio.

Follow Tim Newcomb on Twitter at @tdnewcomb.

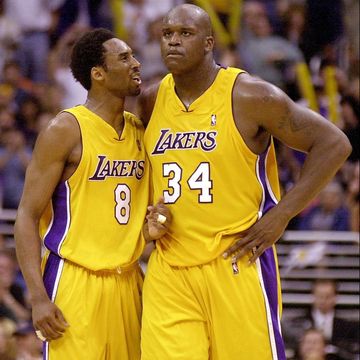

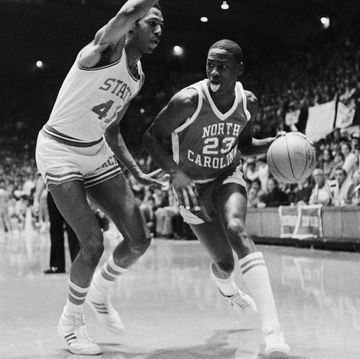

Tim Newcomb is a journalist based in the Pacific Northwest. He covers stadiums, sneakers, gear, infrastructure, and more for a variety of publications, including Popular Mechanics. His favorite interviews have included sit-downs with Roger Federer in Switzerland, Kobe Bryant in Los Angeles, and Tinker Hatfield in Portland.