In the middle of San Francisco’s Mission district, an area perhaps best-known for infant-sized burritos and a confluence of hipsters, there’s a stuffed Sasquatch hanging from the ceiling of a small storefront. It’s a rainy afternoon, yet people scuttling down the street stop dead in their tracks, peer into the window, and come in to marvel at the creation, which incidentally is neither the strangest window display in this neighborhood, nor for this particular shop.

We’re at the headquarters of Betabrand, an internet clothing company that’s made its mark by being a bit out there. Some of its greatest hits include "executive" hoodies aimed at wannabe Mark Zuckerbergs, pants and sweatshirts designed to look like disco balls, and now yoga pants for women designed purposefully to fool people into thinking they’re formal attire. The "dress pant yoga pants" have quickly become Betabrand’s top-selling product of all time, something that took the company by surprise.

"Many women would wear yoga pants to do everything in life."

"Many women would wear yoga pants to do everything in life — even to get married — but they’re sort of prohibited in workplaces," says Chris Lindland, CEO and founder of Betabrand. "This product is going to challenge dress codes."

Metaphorically, the pants and the company are one and the same: they’re challenging normal with quirk, and if you’re not paying close attention, you’ll miss the joke. But what makes Betabrand particularly noteworthy is in what’s happening behind the scenes.

The company is designed like a startup, one that brainstorms ideas and does all its prototyping on-site, a combination that can turn an idea discussed during a morning meeting into something that’s sewn and finished later that day. That process is not something Betabrand invented, nor is it the only company doing it. T-shirt company Threadless, which has since expanded on to make sweatshirts, dresses, cellphone cases, and myriad other products, began with a public proving ground for new shirt designs. A decade later, New York-based Quirky built on that with a more formal editorial process that extends to consumer electronics, kitchen equipment, and clothing.

When Betabrand ideas end up being terrible in prototype form, they’re scrapped or simply retooled. Lindland picks up a yellow and gray knit sweater from a neatly stacked pile and shows it as an example of when things don’t quite work out. It looked great as a mock-up, he says, but when they got it back from an outside contractor, it ended up like a bad Star Trek costume, the kind that wrongly guessed what people might wear in the future. But when it works, you might end up with another potential pair of dress pant yoga pants.

That whole process used to take four months from beginning to end, but is now down to just two months for most products. Lindland says it could get closer to one month, but that would require growing the company far beyond what it is right now. "It’s not Moore’s Law, but we’re close to halving the time," he says. "The average wait for something on Kickstarter is eight months."

Betabrand began as Cordarounds, a Lindland creation that took the typical corduroy pattern and turned it sideways. That started with pants, then expanded into all sorts of other clothing products. Like Apple dropping the "Computer" from its name in 2007, Cordarounds did the same thing in mid-2010 and became Betabrand, a name made to evoke the not-quite-finished nature of what it does while steering clear of its association with just one product.

Betabrand still makes Cordarounds, though the company’s dramatically expanded what it does and how it does it. That includes venturing into the world of crowdsourced clothing ideas, a system that can turn someone’s napkin sketch of a piece of clothing into something the company sells just a month or two later. The dress pant yoga pants, for instance, went from idea to a real product in just five weeks.

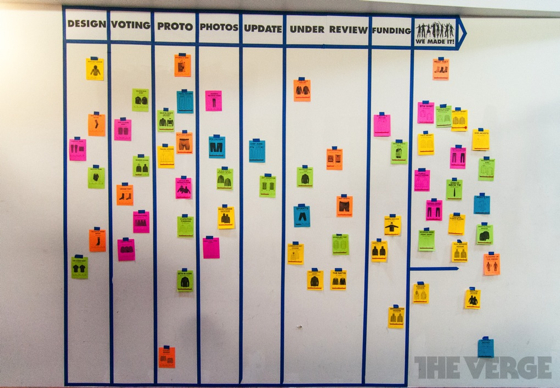

The crowdsourced system opened up last September, and is a combination of both in-house ideas the company is contemplating and ideas sent in by third-party designers. If a design from an outsider makes the cut and goes on sale, that person stands to make 10 percent of net sales. Likewise, shoppers who buy into ideas early on can reap a big discount on the product when it goes into production. This has the potential not only to attract real fashion designers, Lindland says, but also to bubble up products that larger and more established clothing companies see too much risk in and pass over.

"What I found is if you ever interview a fashion designer, they’re going to show you a portfolio with 80 percent that hasn’t been made," he says. "The output of a fashion designer is enormous. You’re designing stuff all the time, and yet a fraction gets made." Instead, Betabrand asks these designers to submit one of those extra creations that larger companies would never make, and potentially make more than they would freelancing a whole stack of ideas.

Ideas without enough interest die quickly

To mitigate some of that risk, Betabrand gauges product popularity before it even has the chance to get made. The "think-tank" is where new product ideas bubble up and get vetted by customers. And if something just isn’t getting enough votes or attention, it dies right then and there.

But some things can be a guaranteed hit, especially if famous people are involved. Lindland and company have turned local San Francisco celebrity chef Chris Consentino, who has worked with Betabrand to create a trio of socks lovingly named "Meat Feet" that look like artisan cured meats, a pair of "Gluttony Pants" with an adjustable waistband that tells you how fat you’re getting (during one meal, even), and a pair of specialty jeans for chefs with custom pockets and a crotch vent to keep line cooks happy.

In that same vein, the company’s latest effort is a NASA-inspired down jacket that was designed to look like a cross between a US space shuttle and the EVA suits worn by astronauts. It’s the creation of a former North Face designer turned Betabrand employee, and uses Tyvek, a material that’s typically used in housing materials, postal service envelopes, and in the crinkly jumpsuits worn by painters and factory workers in clean rooms.

Tyvek is typically used in postal envelopes, not coats

In a promotional video for the space coat, designer Steven Wheeler filmed right outside NASA’s Silicon Valley headquarters, mainly because he couldn’t get in. That changed after designs for the coat went up on the site and made the rounds on the web. "Suddenly all these NASA people are into it," Lindland says. Now the company is working on similar designs inspired by Russian and Japanese spacecraft. All are skirting potential legal issues by letting buyers swap out the logo patches with something else. "We don’t want a cease and desist letter from the federal government," Wheeler joked.

All this leads to the question of what comes next for Betabrand. The company expanded slightly beyond clothing with bags, and Lindland says the next big venture to expect in the next three to six months are shoes. That may seem like a small addition, but it's a risky business. Unlike clothing where there are just a few fits and finishes, shoes come in a dizzying array of sizes and must be ordered in higher volumes. That’s not exactly something the company wanted to take on when it was smaller, or could have dealt with if it turned out to be a failure. At the same time, Lindland says there hasn’t been too much pressure to change a formula that’s working.

"Clothing is great," he says. "There’s enough adventure in the world of soft goods that I don’t think we’ll ever get tired of it."

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/14628946/DSC_0150.1419980351.jpg)