From the November 2011 issue of Car and Driver.

Steel yourself, dear reader, for a bombshell: You cannot buy a new French car in America. You haven’t been able to for 20 years, since 1991, when Peugeot ejected from the United States following a long and nasty sales slump.

Maybe this is not news to you. Maybe those 20 years have seemed a deprived eternity, like an undeserved prison sentence or the wait for drinks in a Parisian restaurant. But chances are greater that you don’t give a rip. The nation that blessed us with the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the Citroën DS also gave us a lot of forgettable automotive garbage. Decades after the Gauls left, questions linger: What have we missed? Why don’t French cars work here? If Alfa Romeo and Fiat can return, should Peugeot, Citroën, and Renault? And if Dominique Strauss-Kahn didn’t grope that New York maid, who did?

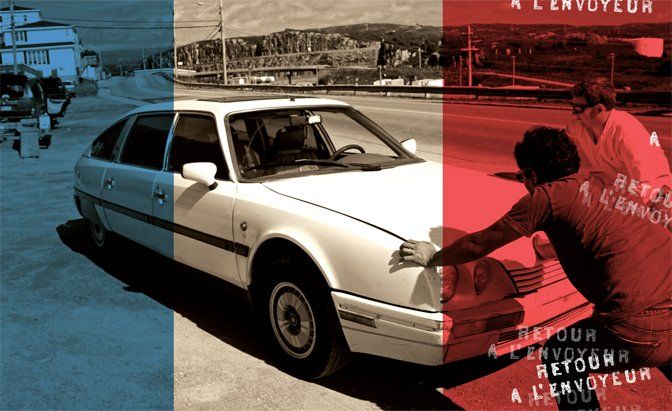

In our search for answers, we found a half-dead Citroën on eBay for the sacré-crapcan price of $1500. Then, in the interest of science, we drove it to France. The goal was to learn something about the cultural divide, or to maybe kill the car and bury it in its homeland. But mostly, we just wanted to give the damn thing back. Ideally in exchange for something still French but better and more reliable, like, say, a pack of cigarettes.

Naturally, there were caveats. First, the Citroën wasn’t an actual Citroën, but a gray-market 1989 import known as a CXA CX25 Prestige. It was built by Citroën but imported by a cabal of New Jersey frogheads called CX Automotive, which makes it both marginally American and the last truly quirky French car sold here. (Hydropneumatic suspension! A single-spoke steering wheel! Mon Dieu!) And second, the France in question isn’t continental France, but an island off Newfoundland called Saint-Pierre. Saint-Pierre and its neighbor Miquelon are French overseas collectives, the only remnant of France’s North American empire: Its 5888 citizens speak French, drive French cars, and buy things with euros.

The CX came from New York City sporting 64,000-ish miles, a three-speed automatic, and more structural rust than the Edmund Fitzgerald. After decades of abuse, the tan interior smelled like a moldy brothel. We dumped it at New Jersey’s Eurocar Imports, a Citroën specialist, and asked for an inspection. We also arranged for a trailer-towing Cadillac Escalade Platinum hybrid to run chase, piloted by videographer Mark Arnold, on the grounds that it had a French name and was almost as weird—6000-pound curb weight, hybrid powertrain, $89,385 sticker—as the CX25.

Interesting trivia: Saint-Pierre remains the only place in North America where a guillotine was used in an execution. Additionally, the island is 1725 highway miles from New York, a car-killing trip that includes two ferries and most of Newfoundland. I roped Car and Driver’s online news editor, Justin Berkowitz, into the drive because he is a mild Francophile and likes watching good things die gallantly.

We prayed the guillotine was still there.

When we arrived at Eurocar Imports, the owner, a British expatriate named Noel Slade, was pushing the CX into a service bay. He announced that the car refused to start, then insisted that we were not idiots for wanting to drive it halfway to Greenland. His customers, he said, are always asking about buying new Citroëns. He does not think this will ever be possible; the French, he said, never got away from speaking to a niche buyer.

Two hours later, the CX was running. A gallon of water in the fuse box—a leak from God knows where—had shorted out a few relays and fuses. Slade hinted that we should avoid getting the car wet. As we drove off, it began to rain. I decided this was a good omen.

Even by French-car standards, Citroëns are odd. The firm’s legendary DS, launched at the Paris motor show in 1955, set the standard: sleek proportions and a slick hydropneumatic chassis that could adjust both ride height and brake proportioning on the fly. The four-cylinder, front-wheel-drive CX, produced from 1974 to 1991, is equipped with a version of the DS’s suspension. When new, our car likely drove well—hydro Cits are often plush enough that you can crest speed bumps at 40 mph and not feel a thing—and looked respectable. Sitting in Jersey traffic, covered in rust-stained white paint and peeling window tint, it just looked like a limousine from some French crackhead’s prom. The suspension worked insofar as it held the body off the ground.

Forty-six-year-old mechanic Joe Carter approached the CX at a Shell station in Toms River. “Who makes this car?” he asked. Frenchmen, I told him. “I figured as much,” he said. “It kind of looks French. Like a nightmare.”

Berkowitz climbed into the CX and started the engine, pressurizing the suspension. The trunk rose to the proper ride height, but the nose stayed slammed, like a dog presenting itself. “It is a nightmare,” I said.

“Oh,” Carter said. “That makes sense.”

In traffic on the Pulaski Skyway, a man in a white Chevy Tahoe pulled alongside: “Eh, boss! This car, it has electronic suspension?” Five minutes later, a dude in a BMW 740i drove up and flashed a gold tooth. “Lift it up!” he shouted. “It’s a Citroën!

Citroën left America in 1975, and our CX was unbadged. But people still remember the brand’s funky calling card. Quelle surprise.

On the New Jersey Turnpike, we slowed for a tollbooth, the car bounding as Berkowitz grew accustomed to the CX’s brakes, which are hydraulically boosted and sensitive enough that you can lock the front wheels with one toe. The toll attendant glanced at the car and visibly recoiled, eyeing our fare money as if it carried the hantavirus.

“Yeah,” Berkowitz said, taking his change, “that’s right. I’m a baller.”

Bored on I-95, I took a good look at the Citroën’s interior. The instrument cluster looks like E.T.’s head, and the turn-signal switch lives on top of the dash. The shift-position lights waterfall down the steering column; the horn is where the headlight switch should be; and the door handles are vertical pistol grips, the latch release a trigger. It’s what you’d draw up if you had never seen a car before. The blank-slate weirdness eventually became kind of charming. Strangely, miles also fixed the suspension’s crankiness. Midway through Connecticut, the CX began riding like a dream, potholes and frost heaves disappearing silently underneath the wheels.

Outside Berlin, Massachusetts, Berkowitz accidentally overfilled the rusty, leaking gas tank. Fuel poured from the tank’s exterior, prompting us to run out and buy a fire extinguisher. We then sat with the Citroën idling, extinguisher handy, waiting for the tank to run down below the leak. A truck driver observed things and offered us a match. “You know,” he said, “to fix it.”

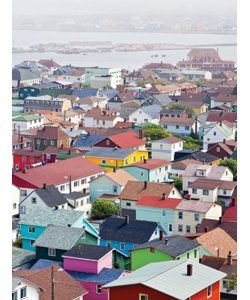

The islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon form a small archipelago off the southern coast of Newfoundland. Originally inhabited by French and English fishermen, the islands were a hot potato for the two European powers for more than 200 years. Retaken by France permanently in 1816, they gained notoriety as a haven for bootleggers during Prohibition. Today, with fish stocks depleted, the islands’ economy is dependent on an annual $60 million injection from the French treasury. Saint-Pierre and Miquelon are as French as Normandy; the corner markets swap your euros for the best baguettes this side of the Atlantic, while teenagers rage in the island discotheque until 5 a.m. If you visit, you’ll get all the evidence of French authenticity you need the moment you arrive, while queuing for a uniquely French bureaucrat tasked with pointing out errors on your immigration form.

The Citroën died unexpectedly in Maine and refused to restart. The problem appeared to be a bad crankshaft-position sensor, which a few phone calls indicated was available but would have to come from (mainland) France. We pushed the 3200-pound CX onto the trailer, cursing the whole way. Save for a few triumphant, optimistic returns to the highway—It runs! It doesn’t! It’s being pushed again!—it would spend most of the rest of the trip lashed down behind the Cadillac. It could not even be relied upon to be reliably unreliable. Our plan subtly shifted sometime around the 600-mile mark from trading the heap for a tasty pack of Gauloises or a jaunty beret to just dumping the thing and running.

It’s difficult to discuss French culture without lapsing into cliché, so let’s just get that out of the way: Arrogance. Cheese. Mimes, moles, indifference, bad waiters, great restaurants.

Also Napoleon. A week before collecting the CX in New York, I watched a documentary on the French Revolution. Suitably motivated, I leaped onto the internet and bought 40 fist-sized stickers featuring a reproduction of Antoine-Jean Gros’s 1796 painting Bonaparte at the Pont d’Arcole. I would like to admit to being sober during this purchase, but I wasn’t. Also, after eight bottles of Kronenbourg 1664, the term “French emperor” causes giggle fits.

This is the problem with viewing France as an American: We’re stuck halfway between four-star restaurants and laughing at an egomaniacal tree stump who tried to take over the world. Most people don’t have enough cultural touchpoints to develop an opinion. Almost everyone I met at fuel stops seemed to think French cars shouldn’t come back to America, but they didn’t really know why. Since the CX was running intermittently, I spent most of Nova Scotia in the Cadillac, ruminating on the dignity of surrender.

Newfoundland is big; it took us an entire day to cross it, nearly all of which was spent in the Cadillac. The locals had impenetrable English accents (“Oohwallgooah! A Cirroan!”) and were impossibly friendly. They eyed the Escalade warily at gas stops, as if it were somehow dangerous.

We arrived in Fortune, the Saint-Pierre ferry town on Newfoundland’s southern coast, at 1 o’clock in the morning. Berkowitz, driving the Escalade, stumbled upon a parking lot full of islander cars, a mix of American and European iron wearing French plates. High on sleep deprivation, he danced around the lot, yelling out rare, Europe-only model names (“Dacia Sandero! Dacia Sandero!”) and waking half the town. Caught in the moment, I tried starting the Citroën. It cranked endlessly.

Problem: The CX’s repeated problems—large, small, and stinky—along with weather delays on the Nova Scotia–to–Newfoundland ferry meant we missed the weekly car ferry to Saint-Pierre. Solution: The Citroën, now almost reliably immobile, was refused passage on the Saint-Pierre boat anyway—a most uncharitable way to treat one of your own fallen, we thought. The daily passenger ferry tootled us to France in 90 minutes, and we walked out of customs to find a parking lot full of new Renaults, Peugeots, even a Ford F-150 SVT Raptor, all with European plates. Tiny, brightly colored houses were everywhere. It was like stepping into Willy Wonka’s factory, only all the Oompa-Loompas spoke Parisian French and resented your fat, rude American face.

Left without wheels, we did a walking tour of Saint-Pierre’s tiny downtown, hunting for interesting car dealers. (The Peugeot franchise is a gas station that moves more than 50 cars a year; the Citroën dealer is also a home-and-garden shop called “Derrible Industrium,” which sounds suspiciously like “terrible industry.”) The island’s 70 miles of roads are narrow and short, and the speed limit rarely tops 50 km/h. In other words, a pretty suitable place for cars that don’t move under their own power. A burned-out Peugeot 206 sat on blocks outside our hotel, and a man in a screaming-chicken–clad Pontiac Firebird almost ran me over while street racing at midnight. I tried to throw my beret at him, then realized I wasn’t wearing one. Wine may have been consumed.

France is a weird place.

Suitably impressed, we returned to Fortune the next morning. The Citroën started one last time, rolled off the trailer, and died five minutes later, never to restart. And it got me thinking.

Our particular French car was a raging pile of garbage, but its crappiness couldn’t hide a baked-in charm. The CX was a giant middle finger to convention, a vive-la-différence souffle of cliché (a cigarette lighter for each door!) and cleverly backward engineering. In a world full of automotive sameness, it stood out. Why don’t French cars work in America? It’s likely that French carmakers, individual to a fault, never bothered to understand our market or tweak their offerings to suit it. But that doesn’t mean the potential wasn’t there. Heck, in 1989, some optimistic chump—er, tastemaker—took a chance on our CX, paying more than $400 every month, for 35 months, to lease a car that was essentially a factory-built orphan. That person saw something. And he wasn’t the only one.

Sadly, we weren’t able to give the CX a proper funeral within sight of Saint-Pierre. The Fortune fire department offered to burn it but later backed out. We also discovered that the car didn’t float, so sailing it home to Europe was out of the question, as was towing it into the Atlantic for a scuttling. The guillotine was nowhere to be found.

We ended up dragging the CX—dead starter motor and suspension stuck on full-low—back to New York. Wedging the car onto our rental trailer for the return trip, we discovered a subframe so rusty that one suspension member was about to fall clean off.

So, failed by our car and rebuffed by those who refuse to bring in their own trash cans, we hauled the Citroën to a Long Island junkyard, where a man who didn’t know what it was forklifted it into the crusher. Scrap.

I felt like I had learned something, but I also felt a little guilty. Then I flew home and drank a bunch of Kronenbourg while searching the internet for used Peugeots. Suddenly, I felt a lot better.