By Sep. 29, peaceful protesters had been clogging Hong Kong’s downtown for less than a day, but to the Chinese Communist Party this already smacked of ingratitude. Here’s an excerpt from an editorial that ran that day (link in Chinese) in the People’s Daily, the party’s official mouthpiece, entitled “No one cares more about Hong Kong’s future destiny than the entire Chinese people”:

Since 1842, when Hong Kong was reduced to being a British colony, our fellow citizens of Hong Kong were but second- or third-class citizens suffering unequal treatment. During the 1950s, anti-colonial liberation movements roiled its colonies and Britain bought off its people’s will, and yet Hong Kong’s political reform plan was unfairly dismissed as “excessively dangerous.” In 150 years, the country that now poses as an exemplar of democracy gave our Hong Kong compatriots not one single day of it. Only in the 15 years before the 1997 handover did the British colonial government reveal their “secret” longing to put Hong Kong on the road to democracy…, creating a not inconsiderable gulf between the mainland and Hong Kong. Yet it was only after the handover—and thanks to none other than the Chinese central government’s diligence—that Hong Kong could begin to hope that within just two decades it would get to elect its chief executive through universal suffrage. Who has the real democracy, and who has the fake democracy—compare the two and judge.

Of course, this argument doesn’t change the fact that the Chinese government’s version of “universal suffrage“ requires that Hong Kong voters pick from candidates Beijing has essentially selected for them, reneging on past promises.

That aside, the Communist Party’s new pet argument seems to make some sense—or at least, it would have until recently. In the last couple years, however, the British government has declassified a cache of colonial records that tell a very different story.

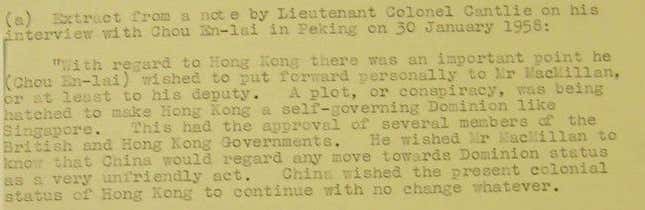

Take for instance this document, which describes what British lieutenant-colonel Kenneth Cantlie relayed to British prime minister Harold MacMillan about his conversation with premier Zhou Enlai in early 1958:

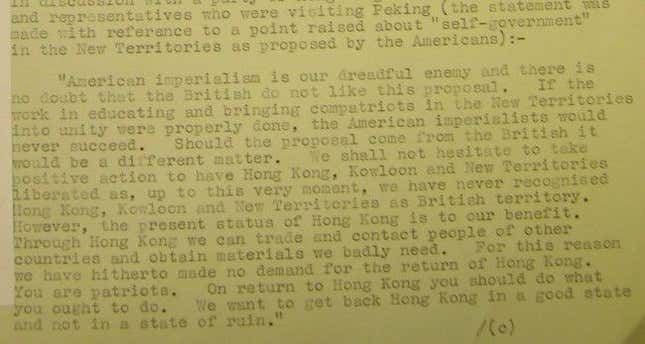

In it, Zhou says Beijing would regard allowing Hong Kong’s people to govern themselves as a “very unfriendly act,” says Cantlie. Not long thereafter, in 1960, Liao Chengzhi, China’s director of “overseas Chinese affairs,” told Hong Kong union representatives that China’s leaders would “not hesitate to take positive action to have Hong Kong, Kowloon and the New Territories liberated” if the Brits allowed self-governance:

These documents—which, perhaps unbeknownst to the People’s Daily, Hong Kong journalists have been busily mining (link in Chinese)—show that not only were the Brits mulling granting Hong Kong self-governance in the 1950s; it was the Chinese government under Mao Zedong who quashed these plans, threatening invasion. And the very reason Mao didn’t seize Hong Kong in the first place was so that the People’s Republic could enjoy the economic fruits of Britain’s colonial governance.

This revelation suggests that the Chinese government’s current claims of democratic largesse are somewhat disingenuous, says Ho-Fung Hung, sociology professor at Johns Hopkins University.

“The whole argument that Beijing’s offer is better than the British’s—it no longer holds,” he tells Quartz. “Beijing can no longer say there were bad things during colonial times because it’s now been revealed that it was part of the force that maintained the status quo in Hong Kong. Beijing is partially responsible for the lack of democracy in Hong Kong before 1997.”

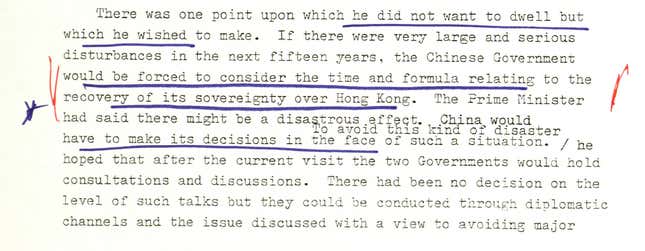

It’s long been known that in the 1980s, once the Brits knew they were going to be leaving and tried to speed up democratic reform, the Chinese government threatened them not to, notes Hung (a point to which the People’s Daily editorial obliquely refers).

In the early 1980s, when prime minister Margaret Thatcher began negotiating with China’s leaders—president Deng Xiaoping and premier Zhao Ziyang—what grew into the Sino-British Joint-Declaration of 1984, Britain had leverage. Treaties signed in the 1800s stipulated that the Brits were only to hand back the northern swath of Hong Kong called the New Territories—and not Hong Kong island or Kowloon (i.e. the major financial and commercial areas), which China also wanted. Beijing also needed the handover to go smoothly in order to convince Taiwan, an independent island state that it nominally laid claim to, that the “one country, two systems” approach could work. In addition, Hong Kong was still a major financial center and trade hub for China too.

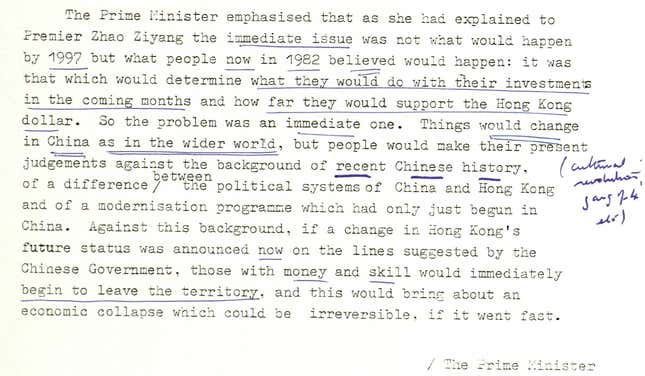

But China had leverage too. In fact, in 1982, when negotiations began, the Hang Seng Index was already shaky due to fears that if China took over, the Communist Party would gut Hong Kong’s rule of law or nationalize wealth, causing the market to crash and capital to flee:

The Brits needed to calm markets and ensure financial stability. That meant making sure the handover agreement protected British financial interests. But as documents from Thatcher’s archive declassified in 2013 reveal, it also meant publicly cooperating with China. In the following memo (pdf, p.3), Thatcher tells Deng that the issue wasn’t what happened in 1997, but what everyone in 1982, when they were talking, expected to happen:

And here’s an example of Beijing’s threats to British diplomats on preserving Hong Kong’s status quo, from the same memo recording Deng and Thatcher’s discussion (p.10):

What the documents from even earlier show is that this showdown—Brits floating democracy, Chinese leaders threatening to invade—had been going on since the 1950s, three decades before we previously knew.

Why did neither ever happen? Hung says that the Brits wanted to make sure they’d protected their economic interests before they departed, much the way they did in Singapore and Malaysia. And when Mao founded the People’s Republic of China in 1949, he and Zhou Enlai decided not to seize Hong Kong—which the British at the time expected—because the capitalist territory was their lone source of foreign exchange and a strategic portal for manufacturing trade that would eventually drive China’s double-digit growth. As the newly declassified documents reveal, China’s leaders explicity wanted to “preserve the colonial status of Hong Kong” so that the People’s Republic could “trade and contact people of other countries and obtain materials” it badly needed.

Both the British and the Chinese governments benefited from the nearly 50-year deadlock of Hongkongers seeing neither democracy nor an invasion. But as the recent protests eerily hint, this limbo can’t endure forever.