Was Piketty wrong about inequality?

- Published

- comments

The last three decades have seen huge changes in the global economy.

Three trends have dominated: falling interest rates, weak wage growth and rising inequality.

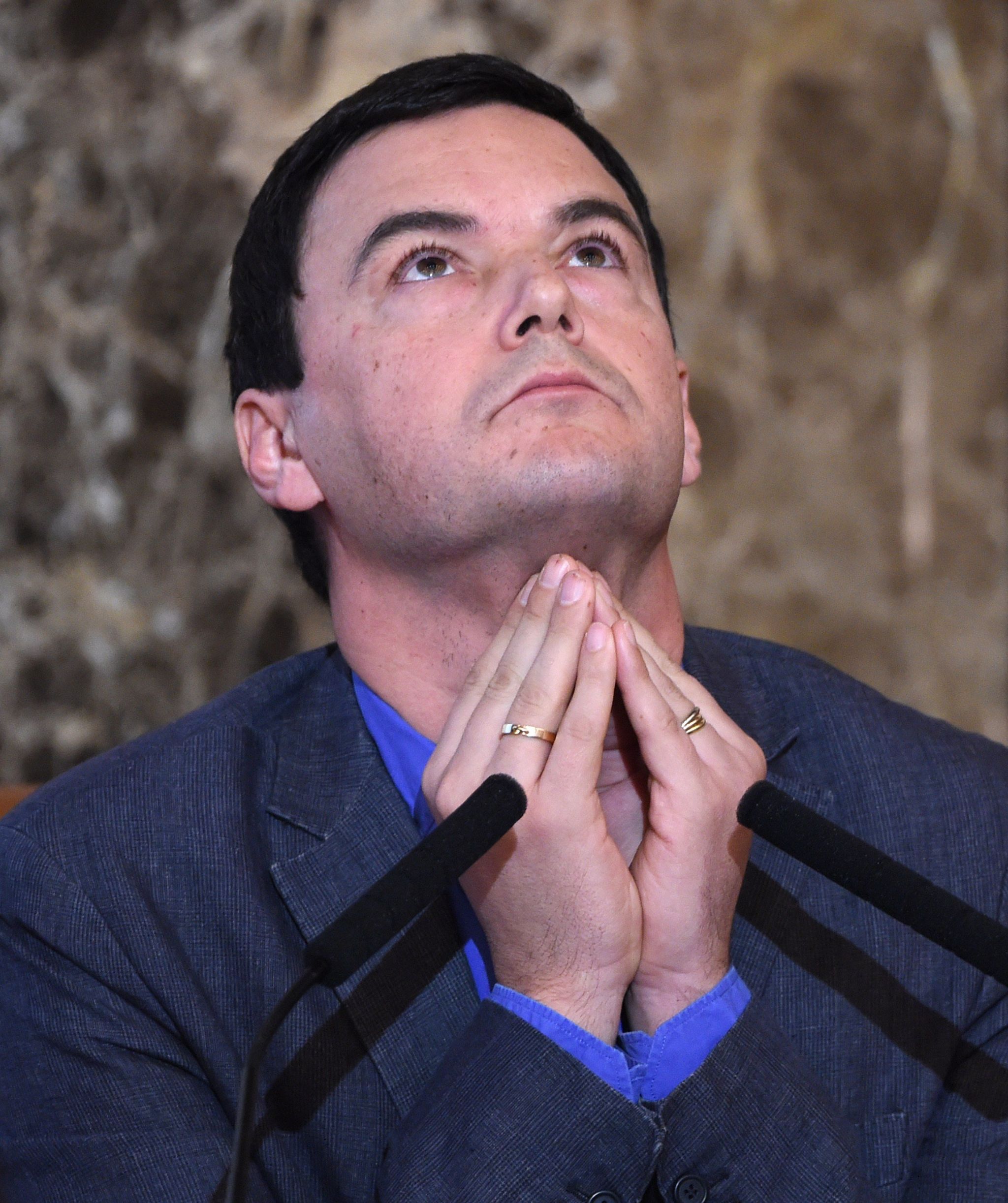

Documenting the last of these trends made the French economist Thomas Piketty an unlikely best-seller.

But might these trends be about to reverse? Is Piketty wrong to worry about rising inequality?

A new note from investment bank Morgan Stanley - co-authored by former Bank of England chief economist Charles Goodhart - thinks he might be.

For Goodhart and the Morgan Stanley team, the real story of the world economy since 1970 is to be found in demographics.

The world entered what they term a "demographic sweet spot" which had profound economic impacts, but that sweet spot is coming to an end.

The sweet spot began in the advanced economies around 1970, as those born in the post-war baby boom entered the workforce amid an era of falling fertility rates and rising longevity.

World population growth was running at brisk pace of 2% per annum in the 1970s and 1980s and has slowed since 1990.

Crucially, the amount of people of working age rose relative to both dependent children (driven by a falling fertility rate meaning fewer babies) and to dependent older people.

Even as populations grew, the global percentage of working age people rose from around 55% in the mid-1960s to around 65% by the turn of the millennium.

The advanced world's demographic bounty was then turbocharged by the entry of China and the former Soviet bloc into the global economy after 1990.

According to Morgan Stanley's numbers, the global labour force more than doubled in the space of just two decades.

That was - in the parlance of economics - a huge positive supply shock to the global supply of labour.

And one that had a major impact on the structure of the world economy, as I've written before, the world we live in today was shaped as much by Mikhail Gorbachev and Deng Xiaoping as by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

But the entry of the formerly-communist (or in the case of China still nominally communist) countries into the world economy was a one-off shock, it isn't about to be repeated anytime soon.

Meanwhile the share of the population who are working age is going into reverse, as a lower birth-rate in the past and seemingly ever-rising longevity begin to bite.

In the advanced economies it is forecast to fall from above 65% today to closer to 60% by 2030.

In other words: after three decades, demographic trends are turning.

After the sweet spot

Morgan Stanley argue that those three decades of demographic change drove the three great trends of falling real (that is accounting for inflation) interest rates, weak wages and rising inequality.

If the demographics turn, then so to might these trends.

We've been living through a global labour glut for decades. And that huge increase in the global supply of labour might explain those long running trends.

A larger supply of global labour will have pushed wages down (and note that the process of globalisation - the increasing integration of the world economy - meant that this did not require immigration: the ability of firms to move production to lower-waged countries was far more significant than the ability of the lower-waged themselves to move jurisdictions).

The glut in the labour force also, according to Morgan Stanley, lowered the returns on labour relative to the returns on capital which (all things being equal) will have acted to increase inequality.

It stands to reason that if the relative return on working, as opposed owning, capital fell, then the owners of assets will have done comparatively better.

The demographic sweet spot also may have driven interest rates lower.

Both through creating a disinflationary impact through weaker wage growth and through a global increase in savings (China's households and firms both save extraordinarily high amounts of their incomes relative to those in advanced economies) that pushed interest rates down.

The end of the "sweet spot" - which may have already started - could see all of this reverse.

The end of the global oversupply of labour could see real wages begin to rise as the returns on labour fall, a change in global savings behaviour as the population ages could push interest rates up in a meaningful way for the first time in decades and - as the returns on labour relative to capital begin to pick up - we might start to see inequality fall.

This would not only prove Professor Piketty wrong but would also represent a huge structural change in the global economy.

Worrying about the wrong thing

The factor that might change the above analysis is one on which Morgan Stanley describe themselves as "agnostic" - technological innovation. As they note, it is hard to predict and sometimes even harder to measure.

Whether or not Morgan Stanley are correct to pin so much on demographic change, there is little doubt that the global demographic picture is changing relatively rapidly.

In the advanced economies, an aging population and declining birth rates mean that the dependency ratio (the ratio of those of working age versus the old and the young) is set to start rising sharply.

Demographics matter. And one look at the projections for the advanced economies is enough to make me ask if one of the great economic worries of the day is entirely placed.

Rather than fretting about the "robots taking all out jobs" (the worry that technology is destroying jobs quicker than we can adapt), it's perhaps better to worry that "the robots aren't taking our jobs fast enough".

Because faced with an aging population and a rising dependency ratio a few more robot workers might be very useful indeed.